In Search of Eternal Light – The World of Cho Hyun-ik’s Art

_mixed%20medi.jpg)

_mixed_med.jpg)

_mixe.jpg)

Lee Jin-myung (Curator of Kansong Art and Culture Foundation) 2015

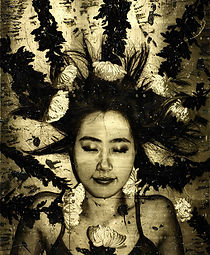

The real allure of Cho Hyun-ik’s art can be better appreciated by dividing his work into two aspects and finally synthesizing them again. The first aspect is external. As the artist delves into the depth of painting, the realm of his art as a painter is extended. This does not mean that any element of installation or video art invades the territory of painting but rather that painting itself spreads to the domain of installation or video art with its own motivation and purpose. Upon a closer examination of his work, we discover a solitary woman portrayed on an iron plate. Despite the cold material property of iron this woman gives off feelings of ecstasy, the joy of love, faith, and some sort of fieriness. This woman is a protagonist at the altar.

We cannot help but recall images of Gustav Klimt's The Kiss and Judith. What come across our minds after Klimt’s ecstatic love is the silk funeral banner unearthed at Mawangdui in China. Within this precious silk painting in gray lay icons of crows, toads, the sun, and the moon. This painting dating back to about 150 B.C. obviously demonstrates that painting is a human activity based on rituals and beliefs. The crow may stand for reason and information whereas the toad perhaps refers to the moon’s yin energy and material property. This two meter high painting is a superb description of all the affairs that take place in the heavenly world, the earthly world, and the underground world with terse symbols and depictions.

Another work of art worth considering is the ancient painting of Fuxi and Nuwa produced in the Former Han Dynasty in China. This painting is a representation of the creation of heaven and earth. Fuxi, the male deity on the right, is holding a square with his left hand whereas Nuwa on the left carries scissors in her right hand. They put their arms around each other’s shoulders, sharing a single skirt. The lower half of their intertwining serpent-like bodies is quite similar to that of intertwining DNA. Their woven bodies are a metaphor for the existence of harmony in the world and the creation of all things. This painting demonstrates how the ancient Chinese believed the world to be in harmony between man and woman, the perfect unity of souls, and sexual intercourse. Fuxi’s square represents ideas and plans, the cerebral and spiritual. This is the world of theoria in ancient Greece. In contrast, Nuwa’s scissors are a metaphor for the practical driving force that cuts all of the things based on Fuxi’s plan. This is the world of praxis. The outer appearance of the women in Cho’s works reminds viewers of those in Klimt’s paintings while calling up images of Mawangdui and Nuwa.

Cho considers the underlying force that constructs the world as being not masculine, contemplative, and reasonable but feminine, sensuous, and practical. The Tao Te Ching by Laozi consisting of 5,000 Chinese characters is full of eulogies to women. The “valley-spirit” (谷神) Laozi referred to may be a metaphorical expression of the “Tao,” a concept signifying the principle forming the world. Many scholars plausibly translate this as a woman’s vagina or womb. The valley-spirit will not die. (谷神不死) This signifies that women’s productivity is undying so it is like a heavenly virtue. Laozi refers to “Tao” (道) as “xuanpin” (玄牝) meaning “a profound female” or “heavenly mind.” So the “gate of profound woman” (玄牝之門) is without doubt a metaphor for female genitals giving birth or the mother’s earnest mind. “The Dao is empty, But when using it, it is impossible to use it up. It is profound, seems like the root of myriad things. Blunts its own sharpness. Unravels its own fetters. Harmonizes its own light. Mixes with its own dust.” Laozi wrote in Chapter four of the Tao Te Ching.1) The sentences above can be seen as a eulogy to making something out of nothing or the process of spreading into the phenomenal world in an epistemological sense. Even if interpreting metaphors such as “empty,” “profound,” and “blunts its own sharpness” as women or female genitals, this makes sense. This is the onset of life, a fusion of square and scissors, and an aggressive gesture to alleviate keenness with peace. The subject of giving birth to, nurturing, and inheriting the world is the woman. The reason why artist Cho lauds women and sets an altar is due to such an insight.

The cold iron plate may stand for the sharply cut scissors Nuwa is holding. The image of a warm, beautiful, and captivating woman intimates Nuwa’s productivity and the valley spirit. This implies the infinite virtue female genitals retain. The true teaching by Socrates can be found in the path of Kalokagathia, a phrase used to describe an ideal of personal conduct and the realization of truth, goodness, and beauty. Plotinus lent all value to the virtue of realizing that all are one and practicing this principle. Korean Buddhism thinks highly of practicing the six perfections or paths to transcendence whereas Korean Confucianism teaches the practice of the “Four Beginnings” (四端), benevolence, righteousness, propriety, and wisdom as the basis of sagehood. All these are the path of Nuwa. If considering that this is an ultimate path, we can realize that the world Cho has depicted is not merely the world of eroticism. We can understand why he tries to reconcile eroticism with religious sublimity and turn coldness to warmness. When we join his world and we feel and imagine it more, our everyday life becomes deeper and more significant. The “eternal light” he refers to is not the light of logos the West argues for but the light of modesty that enables us to feel gratitude to our roots.

Since the beginning of 2015, Cho has made public paintings that draw viewers, recent magic-like shadow works, and works combining painting with installation. The basis of such works is his consistent effort to balance Western physical experimentation with Oriental, elemental, and cosmic thoughts. Cho has been a disciple of Mircea Eliade, a philosopher of religion and anthropologist. Eliade referred to the mountain, a place where a harmonious encounter of earth (woman, mother) with heaven (god) is made as the “axis mundi,” or the world center. This mountain is the birthplace of shamanism, bridging earth and heaven. The arts and religion are derived from shamanism. We are still dependent on the arts and religion for some invisible strength even in our modern scientific age. As in paintings excavated in Mawangdui and ancient painting of Fuxi and Nuwa, mankind has discovered ways to live in shamanism and this aspect will never come to an end. Shamanism can be defined as an earnest gesture to express modesty toward all things in the world. It thus resembles the mountain. Although Cho portrays women and sets an altar sensuously, he also resembles the mountain. If we interpret his work as an expression of his devoted care for and modesty toward the world, we may come across his work with more pleasure.

-------------------------------------------------------

1) Laozi, Tao Te Ching, “道沖,而用之或不盈。淵兮,似萬物之宗。挫其銳,解其紛,和其光,同其塵